We want to identify fingerprinting attempts by counting the number of different APIs employed by a page, especially those not frequently used for benign purposes. This blog post introduces a new fingerprinting protection mechanism - FingerPrint Detector (FPD) available in JShelter 0.6. This tool allows users to gain more control over browser fingerprinting, which has become an invisible threat to our privacy.

Heuristics as a template for the fingerprinting detection

Mitigation of browser fingerprinting is not straightforward. FPD does not attempt to prevent a script from taking a fingerprint. Neither does FPD falsify a fingerprint. Instead, FPD monitors the APIs that a web page accesses and detects suspicious activities. FPD quickly reacts in case of fingerprint extraction and blocks further web page communication, including storing information.

Several studies over the last decade detected fingerprinting attempts. Many of them used a simple heuristic approach to create a set of conditions. If these conditions are met, suspicious activity is detected. Studies like The Web Never Forgets and A 1-million-site Measurement and Analysis used this approach to measure the real-world occurrence of web tracking. At the same time, they verified the usability of heuristic-based detection. They found the detection effective with a very low false-positive rate. The most challenging part of this approach is a careful selection of detection conditions. Later, studies began to experiment with more sophisticated methods. For example, Fingerprinting the Fingerprinters used machine learning for fingerprinting detection. They managed to achieve even better precision, but at the cost of demanding model training.

For JShelter, we settled down on using a simple heuristic approach, but with a little twist to it. Internet technology is constantly changing, so we want to make our heuristics as flexible as possible. Instead of hard-coding them, we propose a declarative way to describe the heuristics. This concept allows us to make changes with a new release and progressively adapt to the latest changes in the field. For this purpose, we defined JSON configuration files, which contain all the information required for fingerprinting detection. As these files make an input for our evaluation/detection logic, their content directly reflects how JShelter should evaluate websites in terms of fingerprinting.

On closer inspection, the configuration files contain two basic types of entries. Firstly, they define JavaScript endpoints, which are relevant for fingerprinting detection. Secondly, they group related endpoints. For example, we group endpoints according to their semantic properties. Imagine that there are two different endpoints. Both provide hardware information about the device. We can assign both endpoints to a group that covers access to hardware properties in this scenario. The configuration allows clustering groups to other groups and creating a hierarchy of groups. Ultimately, the configuration is a tree-like structure whose evaluation can detect browser fingerprinting.

The whole evaluation process dynamically observes the API calls performed by a web page. Note that we analyse the calls themselves. Hence, the dynamic analysis overcomes any obfuscation of fingerprinting scripts.

The current heuristics are based on many prior studies, our own crawl, and available tools focused on browser fingerprinting.

-

We extracted and modified detection rules from studies like:

-

We reflected traits of known fingerprinting tools like:

-

We utilized knowledge of existing detection tools like:

Keep your fingerprint for yourself

FPD works in three basic phases, monitoring, evaluation and reactive.

Monitoring phase

If the FPD module is active, it locally logs all accesses to crucial JavaScript API endpoints during the monitoring phase. FPD injects custom wrapping code of all suspicious APIs (properties or methods) into the browser when a user visits a page. Hence, the extension observes API calls initiated by the website.

FPD stores the number of accessed calls in the context of a displayed page. It contains all the metadata needed for evaluation. This metadata includes the number of calls for each logged endpoint with a corresponding argument value. Consequently, FPD can tell how often the visited web page called a particular endpoint and the arguments for these calls.

Evaluation phase

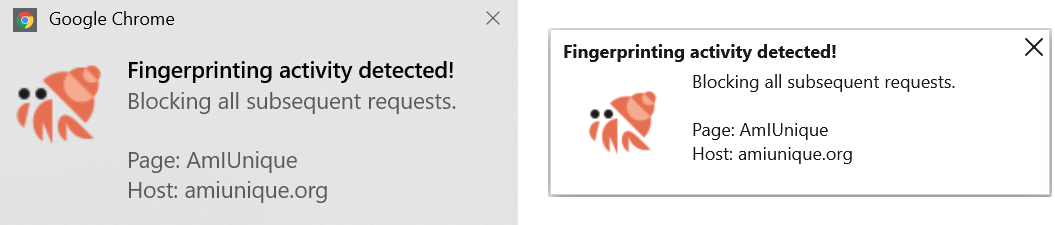

The evaluation phase starts whenever a new HTTP request occurs. FPD counts the fingerprinting score from the observed calls in the past. If the fingerprinting score is above a specified threshold, FPD considers a web page to perform fingerprinting. In this case, FPD warns the user with a notification.

Reactive phase

FPD blocks all subsequent asynchronous HTTP requests initiated by the fingerprinting page in the reaction phase. After that, FPD cleans all supported browser storage mechanisms such as cookies and localStorage. This measure prevents web pages from caching already extracted fingerprints for later transmission. To be clear, blocking of subsequent requests may result in breakage of the visited page. The user can create an exception for the page and add it to a whitelist in this situation. FPD is not active on whitelisted domains for browser fingerprinting. Users can opt in to be fingerprinted on the pages they trust.

For now, we only support whitelisting of the visited domains. However, as fingerprinting is often performed for security reasons and it is more prevalent on login pages, we plan to evaluate if adding a specific behaviour for a URL is a better choice.

Testing fingerprinting detection in the wild

The line between fingerprinting and non-fingerprinting behaviour is very thin. Defining the fixed threshold can easily result in very doubtful results. Hence, the heuristics approach needs careful fine-tuning.

We have made significant efforts to tailor the heuristics in such a way as to target mainly excessive fingerprints that identify users. We also focused on achieving a very low number of false positives for a better user experience. Because of the radical step of blocking subsequent requests, we must ensure that this blocking occurs only in the necessary cases when there is a high probability of fingerprinting.

Additionally, it is very hard to differentiate between benign and fingerprinting usage of a JavaScript endpoint. From the heuristic point of view, setting a higher threshold for fingerprinting behaviour helps FPD reduce false positives. We decided to verify all these assumptions in practice. We tested FPD on real-world web pages and refined heuristics accordingly.

In terms of methodology, we manually visited homepages and login pages of the top 100 websites from the Tranco list. For inaccessible websites at the time of testing, we replaced them with random websites from the top 200 list.

With each access to the tested page, we wiped browser settings to ensure determinism of initial access. As the erasure removed any previously-stored identifier, the visited pages may have deployed fingerprinting scripts more aggressively to identify the user and reinstall the identifier.

To boost the probability of fingerprinting even more, we switched off all protection mechanisms offered by the browser. However, we blocked third-party cookies because our previous experience suggests that the missing possibility to store a permanent identifier tempts trackers to start fingerprinting. To see an impact of a browser on the detection process, we used both Google Chrome and Mozzila Firefox.

We needed the ground truth for web pages employing fingerprinting. We used FPMON and DFPM to create the ground truth. We selected these two extensions because they are the only ones capable of real-time fingerprinting detection. FPMON reports fingerprinting pages with colour. We assigned Yellow colour 1 point and red colour 3 points. DFPM reports danger warnings. If DFPM reports one danger warning, we assign 1 point to the page. For a higher number of danger warnings, we assign 3 points to the page. Therefore, each page gets a fingerprinting score from 0 to 6.

The score of 6 means that both extensions detected excessive fingerprinting behaviour. Web pages with the score of 6 certainly deploy fingerprinting, and FPD must detect such pages. FPD does not detect fingerprinting on Google login pages since FPD heuristics evaluate Google login pages just below its threshold. FPMON and DFPM detect fingerprinting on Google login pages but just above their thresholds. Google login pages occurred six times in total during testing. According to the methodology, these are false negatives. Nevertheless, the final fingerprint is not aggressive enough to provide enough entropy to identify most users uniquely.

The score of 4 means that one extension detected fingerprinting and the other suspects. We classify these web pages as deploying fingerprinting. FPD managed to detect all web pages with two exceptions, Facebook login page and yandex.ru. Both are border-line cases that do not obtain enough entropy, similarly to Google login pages.

The score of 3 means that one extension detected fingerprinting and the other did not detect fingerprinting at all. FPMON and DFPM treat browser fingerprinting differently, so we observed a few web pages with this score. It is questionable how to classify these pages when the reference extensions conflict. FPD does not detect most of these pages. FPD detected fingerprinting only on one of these pages, Paypal login page. We consider this detection justified as we manually checked FPD logs and found clear tracks of canvas fingerprinting. In contrast, FPMON reported negligible fingerprinting signs and did not recognise the fingerprinting attempt.

The score of 2 means that both extensions suspect fingerprinting. We assume that web pages with this score may or may not fingerprint. Nevertheless, the fingerprint is likely not extensive enough to serve as a unique identifier if they do. Moreover, these web pages are prone to misclassification because they may be close to the heuristic threshold. FPD detected two web pages with this score, namely Cloudflare login page and Washingtonpost login page. A closer analysis revealed that both pages use canvas fingerprinting in conjunction with other fingerprinting methods. Interestingly, the reference extensions could not detect such fingerprinting with enough certainty.

The score of 1 means that only one extension suspects fingerprinting, and the other extension does not detect anything. Similarly, for the score of 0 where neither reference extension does detect fingerprinting. According to our testing methodology, FPD should not detect such web pages as fingerprinting. However, FPD detected fingerprinting on ebay.com. Manual inspection showed that ebay.com did fingerprint indeed using canvas fingerprinting, audio fingerprinting and other techniques. Amusingly, the string used by canvas fingerprint says "@Browsers~%fingGPRint$&,<canvas>".

We decided to classify web pages as follows. We considered a page to be fingerprinting when its score is above or equal to 4. We did not count pages with the score of 3 or 2 as fingerprinting because they may not be engaged in fingerprinting in reality. It means that FPD may or may not detect such pages; we do not count such classification as an error in both cases. As discussed above, we manually inspected FPD in these situations. Finally, we consider anything below the score of 2 as not fingerprinting.

-

Number of fingerprinting web pages identified by our ground truth.

- Homepages: 20

- Login pages: 34

-

Number of fingerprinting web pages identified by JShelter.

- Homepages: 20

- Login pages: 30

-

Number of wrong identifications by JShelter.

- Homepages: 2

- False positives: 1

- False negatives: 1

- Login pages: 7

- False positives: 0

- False negatives: 7

- Homepages: 2

At first glance, the numbers are close but not the same. Different heuristic thresholds of the extensions caused the main difference. However, as we found out, the ground truth is far from being flawless. We encountered many exceptions during testing and examined them in detail. In many cases, FPD detects fingerprinting, but the reference extensions do not. For ebay.com, neither FPMON nor DPFM identified the ongoing fingerprinting. We got a very low false positive rate and an acceptable false negative rate in terms of methodology.

We also observed other notable behaviour during the testing. The asymmetry between detection on different browsers was minor but did occur sometimes. However, the difference between browsers should be minimal. We had implemented a mechanism that automatically recalculates heuristics to compensate unsupported APIs. Finally, note that blocking tools like adblockers can significantly reduce the number of positive detections. These tools use filter lists to block tracking scripts before their execution. Using FPD with a filter-based blocking tool can significantly improve user experience and privacy.

TL;DR

We have developed a JShelter module dedicated to browser fingerprinting detection called FingerPrint Detector (FPD). FPD applies a heuristic approach to detect fingerprinting behaviour in real-time. FPD counts calls to JavaScript APIs often employed by fingerprinting scripts. When FPD detects fingerprinting attempt, it will (1) inform the user, (2) prevent uploading of the fingerprint to the server, (3) prevent storing the fingerprint for later usage. We tested FPD on the top 100 homepages and login pages. The results show that FPD identifies excessive fingerprinting behaviour and takes the necessary measures against fingerprint leakage.

Nevertheless, there is always more work to do. The detection heuristics still have room for improvement. The real-world testing yields stimulating research questions. How to define an excessive fingerprint? What fingerprints should be blocked by the extension, and what fingerprints should not? What is the best behaviour (threshold) so that the users find the extension helpful?